3 ways in which your intercultural communication could go wrong

Geschreven door Francine Smink | February 19, 2016A smile on your Japanese business partners' faces is no guarantee for a successful negotiation. The objections of a Russian delegation don't mean that an agreement is out of the picture. The role of intercultural communication in today's global economy should not be underestimated. Is your organisation fully prepared?

“What gets you to “yes” in one culture, gets you to “no” in another”, Erin Meyer writes in the Harvard Business Review of December 2015. Communication - whether in business or privately - will only be successful if you understand your collocutor and interpret his or her verbal and non-verbal signals correctly. In an international context, cultural differences often make this more difficult. If you want to be successful in worldwide business, or if you care about communication within your multinational, please be advised.

“What gets you to “yes” in one culture, gets you to “no” in another”, Erin Meyer writes in the Harvard Business Review of December 2015. Communication - whether in business or privately - will only be successful if you understand your collocutor and interpret his or her verbal and non-verbal signals correctly. In an international context, cultural differences often make this more difficult. If you want to be successful in worldwide business, or if you care about communication within your multinational, please be advised.

Avoiding confrontations

Russians are happy to share a different opinion and they like to be open about this. Don't panic! It is more of an invitation to a lively discussion than a signal that the conversation is going in the wrong direction. The Danes, Dutch and Germans are also used to a level of confrontation, a lack of it even means the relationship is deteriorating. However, a difference in opinion is not considered to be separate from critique at a person in every culture. The last thing you'd want to do is to reject your business partner as a person. That's why, in Mexico, it's better to ask "would you please explain it to me again" than to say "I disagree with you on...". Otherwise, closing that deal or cooperating with that colleague might be a lot tougher than you had thought.

Mind your language!

Small words can make a big difference. Russians, French, Germans, Israelites and Dutch easily use upgraders in disagreements, such as 'totally', 'absolutely' or 'completely'. These can hit Thai, Japanese or Mexicans hard since they are used to downgraders like 'a little' or 'partly'. Learning to use adjectives correctly comes with experience or - in lack of such - practice. It is therefore important to practice realistic situations until one is unconsciously competent.

Showing your feelings

We all know the average Brazilian, Italian or Arab is more expressive than his Western European counterpart. In the eyes of a down-to-earth Dutch person, a business partner who waves their arms and raises their voice during a meeting is very unprofessional. A Parisian delegation would consider this to be normal behaviour, whereas a Swede is used to remain calm and quiet during a meeting. However, if you're in Tel Aviv and your Israeli business partners are sitting in silence, it's time for action. The tranquillity doesn't fit them, so you should interpret this correctly and adjust your strategy.

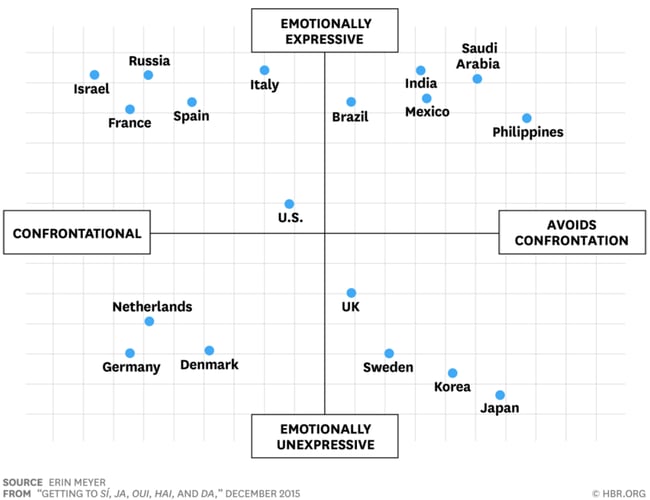

It is a large misunderstanding, Erin Meyer emphasizes, to think that expressive people are confrontational as well. One thing doesn't necessarily mean the other. The graph below shows the difference between different parts of the world clearly. Nationalities are sorted based on how confrontational (horizontal axis) and emotionally expressive (vertical axis) they are.

Therefore, intercultural communication is not simply bowing before Japanese visitors, or interpreting Italians. The verbal and non-verbal differences are often so subtle that experience or practice-based (unconscious) competence is indispensable. In our next blog on intercultural communication we will focus on building trust. Feel free to share your own intercultural experiences in a comment!

TrainTool offers worldwide unlimited practice in communication and soft skills. How? Click below!